With 131 million outbound trips in 2017, China is the world’s largest outbound tourism market, and the top source market for over 20 international destinations. The size of this market and its enormous spending potential (US$258 billion in 2017) comes with huge opportunities, but it also carries risks – any rapid decline of the Chinese inbound market can now affect a country’s entire tourism industry. Whether due to consumer cautiousness, patriotic ire, or government policy, the Chinese outbound travel market has shown itself to be very sensitive to various crises over the past few years. While the causes of many of these situations are far beyond the control of tourism marketers, a good crisis management strategy is still needed. We’ve examined a selection of recent crises, analyzing both positive and negative examples of how they were dealt with.

1. Terrorism and other violence

The Chinese outbound tourism market is particularly sensitive to terrorism and other violent events. For statistics and more information on this, see our article on the impact of terrorism on Chinese tourism. The good news is that the market does recover, as it has for France since 2016, and terrorism seems to delay trips rather than put Chinese tourists off altogether. Despite the risk of terrorism, Israel has been very successful in attracting an increasing number of Chinese tourists over the past several years, and part of this has to do with making safety information very clear and available to Chinese visitors. Addressing risks head on has proved to be a smart strategy for tourism marketing, and not just for the Chinese market – see Colombia’s 2009 ‘The Only Risk Is Wanting to Stay’ campaign.

In France, the passing of time and visible presence of armed police throughout the city, especially at major tourist sites like Notre Dame, has helped bring back visitors from all over the world, including China. However, Paris has other safety perception problems to deal with when it comes to the Chinese market, thanks to several high-profile armed robberies of Chinese tourists. Due to these incidents and their media coverage in China, Paris does not enjoy a good reputation for safety among Chinese tourists. Terrorism – which can affect anyone – is one thing, but crime that targets Chinese can have a bigger impact. In Paris, Chinese police joined French ones to patrol certain areas of the city in the summer of 2014, but this kind of activity hasn’t been reported in France afterwards – Chinese police have also been sent to patrol Rome and Milan in 2016, and Venice and Dubrovnik in 2018.

Chinese tourists are targeted by shops in Paris, but they can also be targeted by thieves

The US also has a safety image problem thanks to frequent mass shootings, and the ample media attention that these receive in China. See our recent article on Chinese attitudes towards traveling to the US for insights on how these fears are not being adequately assuaged. However, one travel brand that has managed a US mass shooting crisis well is Chinese OTA Ctrip – their SOS program helped to locate Ctrip’s customers in Las Vegas within hours of the October 2017 mass shooting, and arranged flights for those who wanted to go home, leaving the very next day.

2. Safety

In July 2018, 47 Chinese tourists were killed when their boat capsized off the Thai island of Phuket. Within a few weeks, around 7,300 hotel reservations had been canceled, and Chinese bookings at Patong Beach dropped 80-90%. Jing Travel reported that the accident is expected to cost US$1 billion in lost tourism revenue, with 670,000 fewer Chinese arrivals now forecast for 2018. This is a stunning example of how sensitive the market can be to safety risks. It’s also a good case study of the right and wrong ways to respond to a crisis.

Initially, the Thai response was not ideal, with the country’s deputy prime minister blaming the Chinese tour operators, and stating “this accident was entirely Chinese harming Chinese.” Whatever truthfulness in this statement – apparently the tourists were advised not to wear their safety vests – it was an insensitive and unhelpful thing to say. Thailand is the primary international destination for Chinese tourists, and a major decline in Chinese visitors will certainly affect the tourism industry there. In response to the ensuing cancellations for July, August and September, Thai travel agents lobbied the Thai government to waive visa fees for Chinese tourists to help contain the damage. By early August 2018, five Thai airports had opened special VIP passport control lanes for Chinese tourists, with mandarin-speaking officials, and it was reported that the authorities were considering offering a new multiple-entry visa for Chinese. Thailand’s tourism police have also gotten involved, taking Chinese media to Phuket to see how boat safety standards were being improved on 3 August.

Despite an initial blunder, Thailand has taken a very swift and proactive response to this crisis in the hope of winning back Chinese tourists as quickly as possible, with moves to make the process of visiting Thailand easier for Chinese citizens, as well as media engagement. Overall, it’s an excellent case study of how to handle a crisis the right way, but it’s still too early to know what the long-term effects of the accident or the response will be.

3. Public relations crises

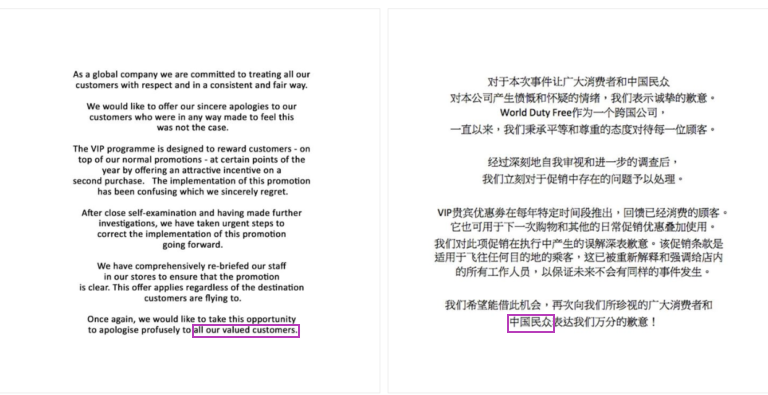

In February 2018, London’s Heathrow Airport came under fire when it emerged that Chinese duty free customers had to spend £1,000 to receive a VIP voucher, whereas other customers only had to spend £79. The story was met with a barrage of angry comments online, as well as editorials in Chinese newspapers. World Duty Free issued a statement, but as it didn’t contain an apology, it only made matters worse. Then, they did issue an apology, which was posted on Weibo, as well as Western social media platforms, and Heathrow also published the apology on their Weibo account. But even this wasn’t enough – a careful reading of the Chinese- and English-language apologies again showed a difference, with the Chinese apology explicitly addressing “the Chinese public” and the English version only referring to “all of our valued customers”. Chinese media and web users were also angry that there were no references to anyone being punished for the discriminatory pricing policy – unlike later in February 2018, when a Thai restaurant manager was arrested for charging higher prices to Chinese tourists.

The takeaway? Avoid discriminatory pricing to start with as a matter of principle, and certainly don’t repeat the mistake that caused the crisis – having one version of a coupon or apology for your Chinese audience and a different version for everyone else – when responding to it.

World Duty Free’s apologies specifically mentioned “the Chinese public” in the Chinese version, but only referred to “all our valued customers” in the English version, provoking more anger

4. Political crises

Political crises can take many different forms. One good example from 2018 is Marriott, which listed Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and Tibet as separate countries in a survey of rewards club members. Then, to make matters worse, an employee running the Marriott International Twitter account ‘liked’ a tweet about the issue posted by a pro-Tibetan independence account. Marriott had its website and booking channels in China shut down for a week as a consequence. The company’s response was an immediate apology, asserting China’s “territorial integrity”, changing their drop-down menus to now refer to “Taiwan, China”, and firing the employee who liked the Twitter post. For Marriott, the crisis was resolved quickly – although their business may now be in trouble in Taiwan. However, Marriott’s gaffe opened a can of worms that is now affecting many other businesses, and forcing international airlines to also change their websites to refer to “Taiwan, China”. The US government condemned Beijing’s demand as “Orwellian nonsense”, but the airlines decided not to risk it, and did comply by the deadline. It’s worth questioning if these enforced references to Taiwan as part of China – which actually has the potential to create some serious confusion for airline customers about visa requirements – may never have come up if it wasn’t for the original Marriott blunder. But now, there’s no going back, and all businesses will need to comply with these strict new naming requirements or risk getting shut out of the Chinese market.

Marriott’s website was blocked for one week in China as punishment for listing Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau as separate countries in a survey

Another kind of political crisis is the one still facing South Korea, which was punished for joining the US THAAD missile defense program in 2017, with a Chinese ban on group tourism and cruises. Chinese tourism dropped 48% in a year, and Jeju Island went from being Asia’s number 1 cruise destination to its 65th. In this case, South Korea was particularly at risk because of its popularity with inexperienced tourists and the number of cruises that went there – a ban on group tourism wouldn’t have such a strong effect on, say, the UK, and a cruise ban wouldn’t affect anywhere outside of Asia. However, Korea has had a hard time coming back, and recovery has depended on daigou shoppers, who resell their purchases in China. This supports airlines and duty free shops, but it does not help the overall tourism industry, especially not attractions. Seoul is also now turning its attention away from China, and courting Southeast Asian tourists instead. But rather than giving up on the Chinese market, a better path to recovery would see South Korea marketing more to independent tourists – with guides to traveling alone, as a couple, or on a girls’ weekend trip (see our China Outbound Travel Pulse episode on travel companions for more on these types of groups). FIT couples’ tourism could especially help Jeju, South Korea’s “honeymoon island.” In contrast to South Korea, Taiwan has had great success with its strategy to refocus on the Chinese FIT market, and provides a good counter-example.

5. KOLs/celebrities

In May 2018, the Intercontinental Carlton Cannes opened a ‘Fan Bingbing suite’ named after the Chinese actress who had stayed there. But Fan has since disappeared in a tax evasion scandal, and the luxury brands she endorses are pulling their advertisements and partnerships.

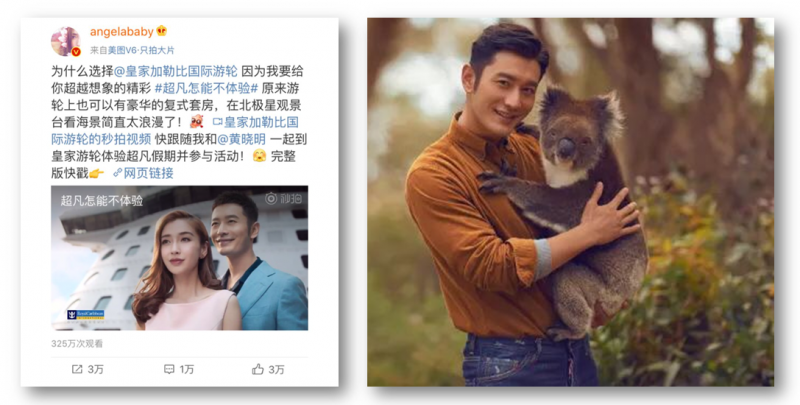

Huang Xiaoming is currently the face of South Australia Tourism and Royal Caribbean International. He’s also recently been caught up in a scandal over stock price manipulation. At present, it looks like Huang has managed to distance himself from any accusations, but what do you do if your KOL falls from grace? Rather than putting all your eggs in one basket with one celebrity, who could ultimately tarnish your brand image, it’s less risky to work with multiple micro-influencers, who will be more cost-effective and potentially have more engaged audiences anyway.

Actor Huang Xiaoming is the face of Royal Caribbean International and South Australia Tourism, but he’s also been implicated in (and subsequently exonerated from) a recent scandal on stock price manipulation

You should also make sure to thoroughly vet any KOLs before you start working with them, and fully understand their reputation in China – the Australian government recently discovered that the same Instagram and gaming stars used to promote public health campaigns and air force recruitment were also promoting alcohol and diet pills, and making racist and misogynistic jokes online. These were not Chinese influencers – who might be a safer bet for clean images – but a good warning against rushing into an influencer marketing relationship too soon. As of September, 2018, there’s now a ‘social responsibility assessment’ ranking for Chinese celebrities that you can consult.

To learn more about crisis management for the Chinese outbound tourism market, join Dragon Trail’s Managing Director – EMEA, Roy Graff, at the ITSS International Travel Security Summit in Jerusalem, from October 7-9, 2018. Find more information on the event here.

Sign up for our free newsletter to keep up to date on our latest news

We do not share your details with any third parties. View our privacy policy.

This website or its third party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. If you want to know more or withdraw your consent to all or some of the cookies, please refer to the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to the use of cookies.